Camilla: You, sir, should unmask.

Stranger: Indeed?

Cassilda: Indeed, it's time. We all have laid aside disguise but you.

Stranger: I wear no mask.

Camilla: (Terrified, aside to Cassilda) No mask? No mask!

— Robert Chambers, ‘The King in Yellow’

*

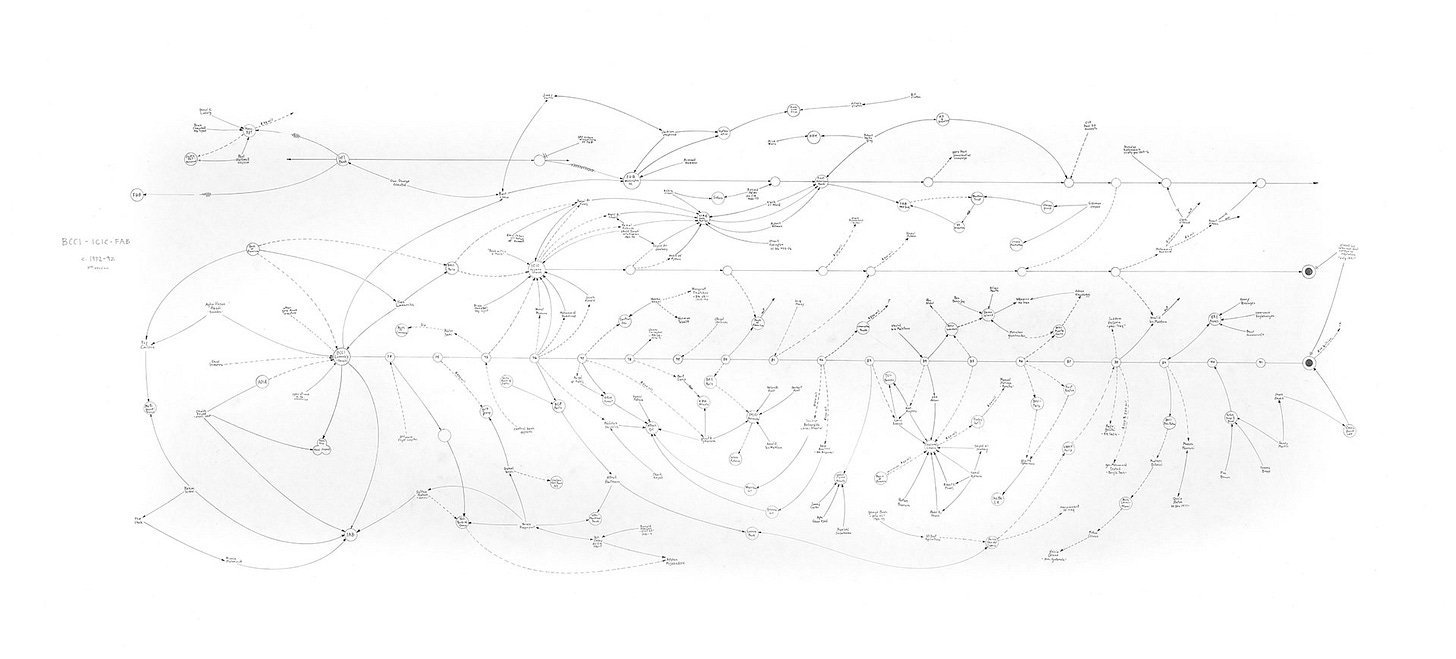

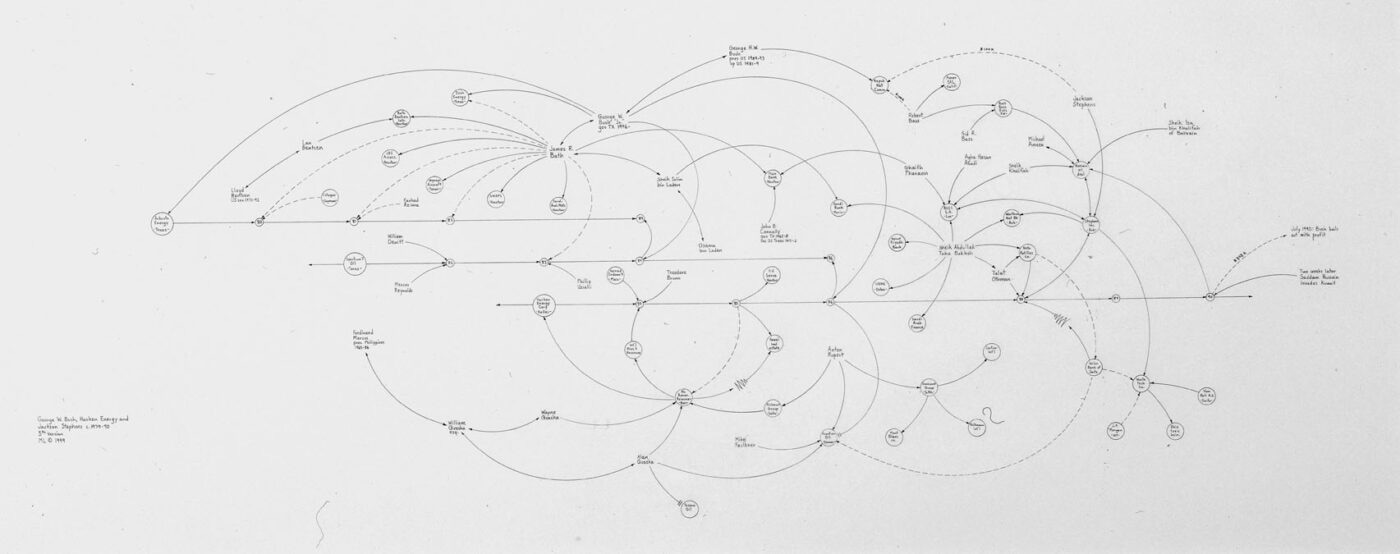

Something radical happens, from time to time, in art. It might even happen quietly, barely a rumble beneath the surface, largely unnoticed until the years pass and its influence permeates. When Mark Lombardi drew his first flowchart in 1987, at the age of 36, it was one of such moments. An artist who couldn’t draw, his penchant for investigative journalism came in use at a time when globalisation had created such vast networks of capital and information transfers that their own complexity rendered them close to incomprehensible.

Lombardi’s breakthrough wouldn’t come until 1996 with the first exhibition of 26 of his works such as “Charles Keating, ACC, and Lincoln Savings” or “Banca Nazionale del Lavoro, Reagan, Bush, Thatcher, and the Arming of Iraq”. The level of detail in his works is breathtaking, obsessive. Nodes of influence connected via threads of vague meaning, all painting a picture of a shadow government of monetary influence. A one-man mission to capture the data and metadata of the world’s under-the-table dealings, his drawings take the shape of ever-expanding kabbalistic trees, their enlightenment limited to the earthly kingdom: from money laundering, to drugs, to arms deals, to shady banks.

Some of his works, like “BCCI, ICIC, and First American Bankshares” above, underwent constant revisions and multiple versions, playing catch-up with new sources of information until one day, in 2000, Lombardi commited suicide in his NY apartment. In the eulogistic words of Jerry Saltz, more than a conceptual artist "he's a sorcerer whose drawings are crypto-mystical talismans or visual exorcisms meant to immobilize enemies, tap secret knowledge, summon power and expose demons". Lombardi’s mission had become to shine a light on the workings of the very real demons that shaped our world. He was the essential political artist of the late 20th Century and, also, a conspiracy theorist.

I remember the airing of True Detective season 1 as a defining moment in TV. The tightly scripted crime miniseries had everything to merit its success, plus a legion of fans fixated on the cynic verbiage of a chain-smoking Matthew McConaughey. It shrouded its central mystery under multiple layers of meaning and created a culty lore that drank from Cosmic Horror authors like Lovecraft, Chambers or Bierce, which of course in 2014 prompted theory after theory on Reddit.

Obsessed with solving a series of murders that had been going on for decades, McConaughey’s detective Rust Cohle was building theories of his own. When he finally shows his ex-partner (Woody Harrelson’s Marty Hart) the result of his independent investigation on the second-to-last episode, it is in the form of a storage unit where the walls have been plastered with disparate pieces of the puzzle, meaningful words, symbols. After all, what are detective cases but the unveiling of smaller-scale conspiracies? What are their “crazy walls” but maps of meaning akin to those Lombardi spent the late third of his life creating?

Aside from its overt occult themes, True Detective was different from many other crime shows in how explicit it was about its conspiracy theorist inclinations. Ultimately, [SPOILER] our heroes tap into the existence of a network of powerful men engaging in pagan sacrifices and child abuse. It is a now all too familiar narrative of the elites preying on the poorest, set in a region devastated by natural disasters, abandonment, and greed.

Every season in the anthology series deals with a conspiracy, in one way or another, as part of its central themes. With season 1 as a tough act to follow, season 2 offers a departure in theme and scope by presenting us with a political conspiracy and a few hardened characters standing hopelessly against it in the vein of a noir ‘Sin City’ storyline. Season 3, on the other hand, learns from the errors of its predecessor and takes the story back to a small-town murder, leaning into the personal struggles of the people wrapped in it.

I can only assume that the people out there who prefer season 3 to both others were smitten with the ‘Serial’ podcast and keep a copy of ‘In Cold Blood’ on their bedside table. Lacking the bombastic action punch of its predecessors, it veers hard towards the procedural, bone-dry presentation of a true crime product. It seems uncomfortable with the idea of a grand evil conspiracy. For the first time in the series [SPOILER] an institution keeping secrets is presented as a source of good. Even though the rich and powerful are able to leverage their influence throughout the season to commit despicable acts, it’s isolated to one or two “bad apples” and everyone else is involved out of incompetence, ignorance, or both.

By losing its conspiratorial themes True Detective lost some of its beauty. Surmounted by the prevalence of A24-style narratives where trauma was the real monster all along, there is something to mourn with the decline of conspiracy theory fiction. There is luridness, sure. It’s part of their mass appeal. Any network of secrets, real or fictional, will convey sordidness where its connections seem more tenuous. But in the Internet age, narratives that works as vast tapestries are perhaps the best way to convey the hidden truths of our world, to shine a light on the complex systems at play.

One of my favorite texts about the topic is Lance deHaven-Smith’s ‘Conspiracy Theory in America’. In big part because, contrary to a lot of literature on the matter, it’s not biased against it by default. Instead, deHaven-Smith goes back to the origins of the term as an opposition to the Straussian idea of “noble lies” and “salutary myths” upheld by the government for the better functioning of society, down to the pejorative use of “conspiracy theories” by the CIA to curb criticism of the Warren Commission Report on the Kennedy assassination. Thus, the conspiracy theory becomes a tool of resistance to what he calls State Crimes Against Democracy —“the type of wrongdoing about which the conspiracy-theory label discourages us from speaking”—.

We can now go back to Mark Lombardi, dead by hanging at the height of his career. Lombardi, found next to a bottle of champagne despite not being a champagne drinker. Lombardi whose “BCCI, ICIC, and First American Bankshares” drawing was privately examined by an FBI agent in the wake of 9/11. And we can see how an obsessive research of the conspiratorial machine can turn one into another node in the flowchart of secrets.

There probably isn’t a State Crime Against Mark Lombardi, much like there isn’t an easy way to defend conspiracy theories wholeheartedly. Soon we meet with the outlandish: the flat Earth, the blood-drinking reptilians. It’s easier to fall back and dismiss the whole thing, much like it’s easier for True Detective to shed its conspiratorial skin and its crazy walls. But this uncritical retreat seems cowardly, navel-gazey. Following a trend of hyper-focus on the identitarian, we turn our analytic skills inwards when we feel overwhelmed by the complexity of the world. Meanwhile, our social media feedback loops are increasingly policed by organizations taking money from the state and military. There is no fighting it without exposing their networks of influence.

The Internet, with its unprecedented amounts of data and its competing narratives, has become the forefront of the information battleground. It’s never been more crucial to engage critically and identify patterns, to gain some insight on the world around us. Conspiracy theories can work as a last resort tool for filtering through what seems never-ending. This is what makes Lombardi’s work so essential: it holds the promise of finding meaning in metadata.

“Are you in the right headspace to receive information that could possibly hurt you?”

More art form the margins of state narratives:

J. G. Ballard’s “The Assassination Of John Fitzgerald Kennedy Considered As A Downhill Motor Race”

Peter Saul’s “The Government of California”

David McGowan’s “Programmed to Kill: The Politics of Serial Murder”